Fentanyl Patches: How They Work, Risks, and What You Need to Know

When you hear fentanyl patches, a prescription opioid pain reliever delivered through the skin via a sticky patch. Also known as transdermal fentanyl, it's one of the strongest pain medications available—used only for severe, long-term pain that other drugs can't control. Unlike pills, these patches slowly release medicine into your bloodstream over 72 hours. That means fewer doses, but also higher risk if misused.

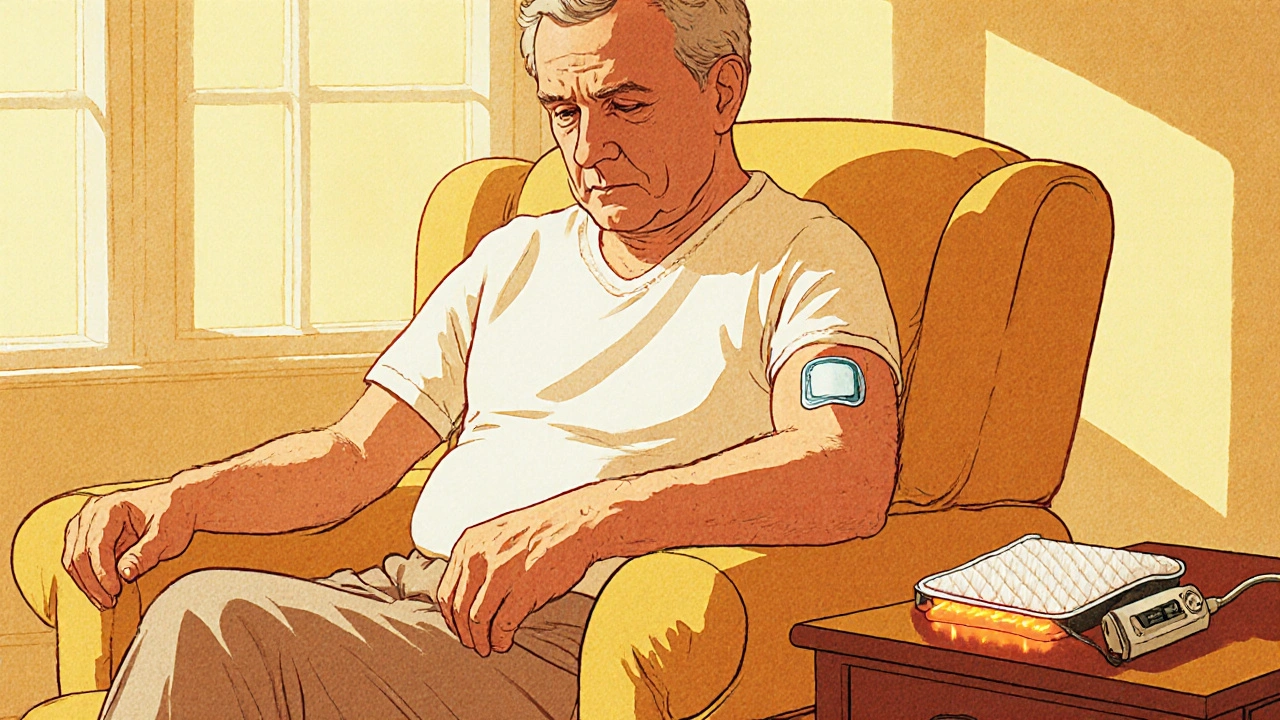

Fentanyl patches are not for occasional pain. They’re meant for people already tolerant to opioids—like cancer patients or those with chronic pain who’ve built up resistance to weaker drugs. If you’ve never taken opioids before, even one patch can be deadly. The dose is precise: too little won’t help, too much can stop your breathing. That’s why doctors monitor patients closely when starting this treatment. The patch itself looks simple—a small square stuck to your skin—but inside it holds enough drug to kill someone who’s not used to it.

Using fentanyl patches safely means following rules you can’t skip. Never cut, chew, or microwave the patch. Heat from a hot tub, heating pad, or even a fever can make the drug release too fast. Don’t apply it to damaged skin. Store used patches folded in half with the sticky side in, out of reach of kids or pets—just one patch can be lethal to a child. And never share your patches, even if someone else has pain. This isn’t like sharing a painkiller from the medicine cabinet. This is a controlled substance with a high risk of overdose, addiction, and death.

People often confuse fentanyl patches with other pain relievers like morphine or oxycodone. But fentanyl is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine. That’s why switching from one opioid to another isn’t simple—it needs careful calculation by a doctor. If you’re on fentanyl patches and your pain changes, don’t adjust the patch yourself. Talk to your provider. Also, never combine fentanyl with alcohol, sleep aids, or anxiety meds. Mixing them can slow your breathing to a dangerous level.

Some users report side effects like dizziness, nausea, or constipation—common with opioids—but others face more serious issues like confusion, extreme drowsiness, or shallow breathing. If you or someone you know shows signs of overdose—blue lips, slow heartbeat, unresponsiveness—call emergency services immediately. Naloxone can reverse it, but only if given fast. Keep it on hand if you’re using fentanyl patches at home.

While fentanyl patches help many manage pain, they’re not a one-size-fits-all solution. They require ongoing evaluation. Your doctor should check in regularly to see if the dose still fits your needs. Over time, your body might need adjustment—or you might need to switch to another option. This isn’t about quitting pain relief. It’s about staying safe while getting relief.

Below, you’ll find real-world guides on how these patches interact with other drugs, what to do if side effects show up, and how to avoid common mistakes that lead to harm. These aren’t theoretical tips—they’re based on actual cases and clinical advice. Whether you’re using fentanyl patches yourself or caring for someone who does, this collection gives you the facts you need to stay safe.

Heat Risks with Fentanyl Patches: How Heat Boosts Absorption and Increases Overdose Danger

Learn how heat boosts fentanyl patch absorption, the overdose risk it creates, and practical steps to stay safe. Real cases, science, and clear safety tips guide patients and caregivers.

view more