Urinary Retention & Spasms Assessment Tool

This assessment tool helps you understand if your symptoms might indicate urinary retention or bladder spasms. It is for informational purposes only and not a medical diagnosis. If you experience severe symptoms, seek immediate medical attention.

Answer the following questions based on your current symptoms:

Your assessment results will appear here after clicking the button above.

This assessment tool is for informational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice. If you experience severe symptoms, seek immediate medical attention.

When you can’t empty your bladder fully and feel sudden, painful twitching in the pelvic area, two things are probably linked: urinary retention and muscle spasms in the bladder or urinary tract. Understanding why these symptoms appear together helps you spot the underlying problem and choose the right treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Muscle spasms in the detrusor or pelvic floor can block urine flow, leading to retention.

- Common triggers include infection, nerve injury, medication side‑effects, and chronic bladder overactivity.

- Accurate diagnosis relies on urodynamic testing, imaging, and a thorough symptom history.

- Treatment ranges from medication and physical therapy to catheter use or surgery, depending on cause.

- Lifestyle changes such as fluid timing, caffeine reduction, and pelvic‑floor exercises often prevent recurrence.

What Is urinary retention is the inability to completely empty the bladder, which can be acute (sudden) or chronic (gradual)?

Acute retention is a medical emergency - you feel a full bladder but nothing passes. Chronic retention may sneak in; you notice a weak stream, frequent trips to the bathroom, or a feeling of incomplete emptying.

Understanding bladder muscle spasms are involuntary contractions of the detrusor muscle or surrounding pelvic floor that create sharp, cramping sensations

These spasms are the body’s way of trying to push urine out when something blocks the normal flow. The spasm itself can be painful and may trigger a cascade that actually prevents the bladder from emptying.

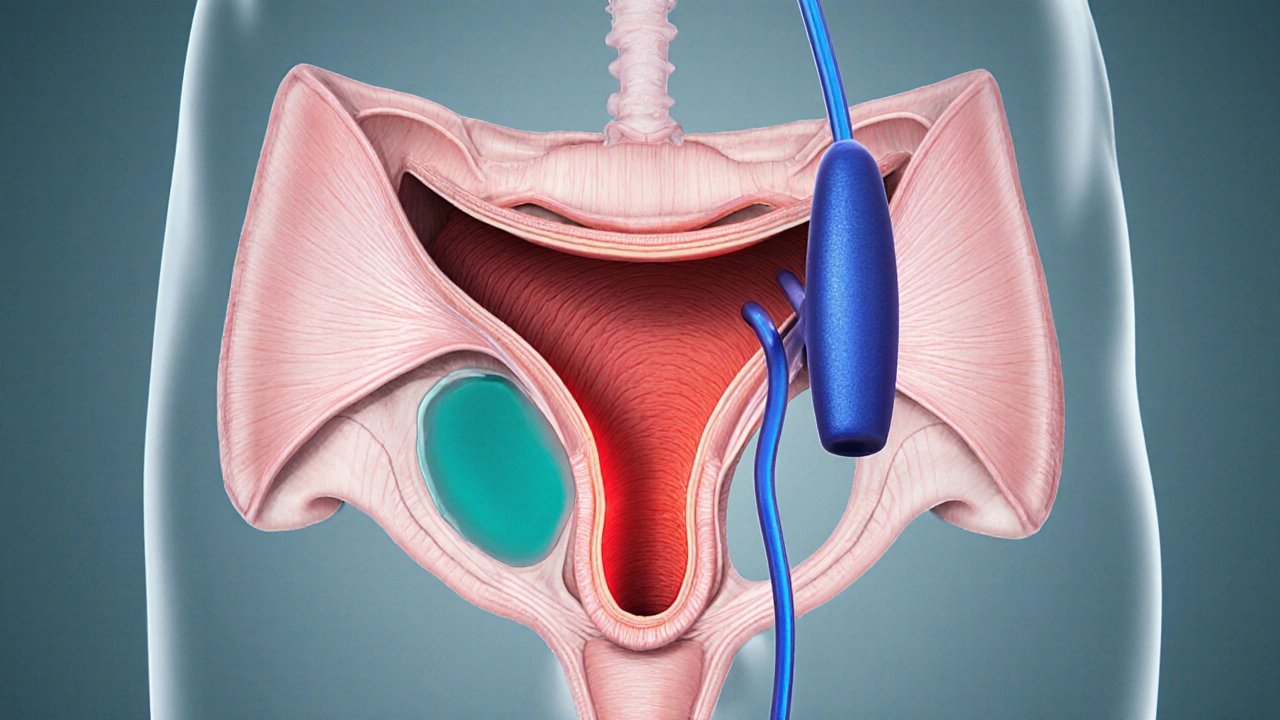

How the urinary tract works

The urinary tract includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The bladder stores urine, while the detrusor muscle is the smooth muscle that contracts to expel urine. Coordination between the detrusor and the sphincter (a ring of muscle at the bladder neck) is controlled by nerves in the spinal cord and brain.

Why Muscle Spasms Lead to Retention

When a spasm occurs at the wrong time - for example, the sphincter contracts while the detrusor tries to push - the urine gets trapped. This mismatch can happen for several reasons:

- Nerve irritation: Damage from spinal injuries, multiple sclerosis, or diabetic neuropathy disrupts the signaling that tells the bladder when to relax.

- Infection: A urinary infection (urinary infection or UTI) inflames the bladder lining, prompting painful spasms that paradoxically block flow.

- Medication side‑effects: Anticholinergics, antihistamines, or certain antidepressants can impair detrusor contractility while still allowing the sphincter to stay tight.

These factors cause what clinicians call “functional obstruction,” where there’s no physical blockage, only a coordination problem.

Common Conditions Linking Spasms and Retention

Several diagnoses sit at the intersection of spasms and retention:

- Overactive bladder (OAB) is a syndrome marked by urgent, frequent urination and involuntary detrusor contractions. In some patients, OAB progresses to retention when the bladder muscle fatigues.

- Pelvic floor dysfunction involves tightness or weakness in the muscles that support the bladder and urethra, often producing both spasm pain and a blocked outflow.

- Neurogenic bladder is any bladder control problem caused by nerve damage, commonly seen after spinal cord injury or in Parkinson’s disease. The nerves may send mixed signals, causing the sphincter to spasm while the detrusor tries to contract.

Diagnosing the Connection

Doctors use a combination of history, physical exam, and specialized tests:

- Urodynamic study: Measures bladder pressure, flow rate, and sphincter activity. It can pinpoint whether spasms are detrusor‑driven or sphincter‑driven.

- Ultrasound: Checks post‑void residual volume (how much urine stays after a bathroom visit). A residual over 100ml usually signals retention.

- Cystoscopy: A thin camera looks inside the bladder for stones, tumors, or scar tissue that might cause obstruction.

- Blood and urine labs: Rule out infection, diabetes, or electrolyte imbalances that affect muscle function.

Treatment Options Tailored to the Root Cause

Because the problem can stem from nerves, muscles, or infection, therapy is often multi‑pronged.

Medication

- Alpha‑blockers (e.g., tamsulosin) relax the bladder neck sphincter, easing outflow when the sphincter is overly tight.

- Anticholinergics or beta‑3 agonists (e.g., mirabegron) calm detrusor overactivity, reducing painful spasms.

- Antibiotics treat UTIs that provoke spasm‑induced blockage.

Physical Therapy

A certified pelvic‑floor therapist teaches relaxation techniques, biofeedback, and targeted stretching to release chronic muscle tension. Studies show a 30% improvement in voiding efficiency after eight weeks of guided exercises.

Intermittent Catheterization

When the bladder can’t empty on its own, a clean intermittent catheter (CIC) inserted several times a day prevents over‑distension and kidney damage. CIC is preferred over long‑term indwelling catheters because it lowers infection risk.

Surgical Interventions

In severe cases, surgeons may perform a sphincterotomy (cutting part of the sphincter) or bladder augmentation to increase capacity and reduce pressure spikes.

Prevention and Lifestyle Tweaks

Even after treatment, some habits keep the bladder happy:

- Limit caffeine and alcohol - they irritate the bladder lining and trigger spasms.

- Stay hydrated but avoid large fluid loads within two hours of bedtime to reduce nocturnal urgency.

- Adopt a “double‑void” routine: urinate, wait a minute, then try again to ensure the bladder empties fully.

- Practice gentle pelvic‑floor relaxation (deep breathing, yoga) especially after long periods of sitting.

Quick Reference Table

| Cause | Mechanism | Typical Symptoms | First‑Line Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| UTI‑induced inflammation | Bladder wall irritation → detrusor spasm | Painful urgency, cloudy urine, low‑grade fever | Targeted antibiotics + short‑term antispasmodic |

| Pelvic floor hypertonicity | Overactive sphincter contracts during voiding | Weak stream, sense of incomplete emptying | Pelvic‑floor PT + alpha‑blocker if needed |

| Neurogenic bladder (spinal injury) | Mixed signals → detrusor‑sphincter dyssynergy | Nocturia, occasional incontinence, high residual | Intermittent catheterization + neuromodulation |

| Medication side‑effects | Anticholinergic drugs blunt detrusor contractility | Slow stream, hesitancy, occasional spasms | Medication review + bladder‑training regimen |

When to Seek Immediate Help

If you experience sudden inability to urinate, severe pelvic pain, or fever, go to the emergency department. Acute retention can damage the bladder wall within hours and raise the risk of kidney infection.

Putting It All Together

The link between urinary retention and bladder muscle spasms is a loop: spasms block flow, retention stretches the bladder, and a stretched bladder becomes more irritable, spawning more spasms. Breaking the cycle means tackling the root cause-whether it’s an infection, nerve issue, or pelvic‑floor tension-and using a combination of medication, therapy, and smart habits.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can muscle spasms cause chronic urinary retention?

Yes. When the detrusor or sphincter contracts at the wrong time, urine can be trapped, leading to a gradual build‑up of residual volume. Over months, this can become a chronic condition if not addressed.

What tests confirm that spasms are the cause?

Urodynamic studies are the gold standard. They measure pressure changes during filling and voiding, showing whether the sphincter or detrusor is contracting inappropriately. Ultrasound for post‑void residual and cystoscopy may be used to rule out physical blockages.

Is intermittent catheterization safe for long‑term use?

When performed with clean technique, intermittent catheterization carries a lower infection risk than an indwelling Foley catheter. Many patients use it for years without complications, provided they follow hygiene guidelines.

Can lifestyle changes reduce bladder spasms?

Absolutely. Cutting caffeine, staying hydrated, practicing timed voiding, and doing daily pelvic‑floor relaxation exercises can lower spasm frequency for many people.

When is surgery considered for retention caused by spasms?

Surgery is a last resort, typically after medication, therapy, and catheterization have failed. Options include sphincterotomy, bladder augmentation, or neurostimulation devices that re‑train nerve signals.

Real Strategy PR

October 12, 2025 AT 19:15It's unacceptable to ignore the obvious link between bladder spasms and retention.

Doug Clayton

October 13, 2025 AT 03:35I think the explanation about nerve irritation really hits home and it makes sense that a spinal injury can mess up the coordination between muscles and bladder it’s a simple cause‑effect chain that many overlook.

Michelle Zhao

October 13, 2025 AT 11:55Esteemed readers, while the treatise expounds upon the neurogenic mechanisms, one cannot help but notice the omission of psychosomatic contributors. The author’s reliance on purely physiological data, though thorough, disregards the profound impact of stress on detrusor activity. In this regard, the discourse appears narrowly confined.

sneha kapuri

October 13, 2025 AT 20:15Whatever, your glorified empathy won’t fix a bladder that’s being hijacked by misplaced nerve signals. People need to stop patting themselves on the back and start demanding proper urodynamic studies now.

Mauricio Banvard

October 14, 2025 AT 04:35When you wade into the murky waters of urinary retention, you quickly discover that the culprits are as varied as a palette of neon paints. First, consider the classic antagonist: a bacterial invasion that turns the bladder lining into a tinderbox of inflammation. The ensuing detrusor spasm is not a mere hiccup but a full‑blown tantrum of smooth muscle fibers. Add to that the pharmacological saboteurs-anticholinergics, antihistamines, even certain antidepressants-sneaking in like covert operatives to blunt muscle contractility. Now, picture the nervous system as a symphony orchestra gone rogue; a misplaced signal can make the sphincter contract while the detrusor strains in vain. Patients with diabetes often suffer from neuropathy, which is the perfect recipe for this dyssynchrony. Meanwhile, chronic caffeine consumption fuels irritability of the bladder wall, turning ordinary urges into a barrage of painful spasms. In the realm of pelvic floor dysfunction, hypertonic muscles act like a clenched fist, refusing to relax even when the bladder begs for release. All of these factors conspire to raise post‑void residual volumes, a silent harbinger of renal jeopardy. The gold standard to untangle this knot is urodynamic testing, which offers a panoramic view of pressures, flows, and sphincter coordination. Ultrasound, though less glamorous, provides a quick snapshot of how much urine is left behind after a void. Cystoscopy can rule out physical blockages such as stones or tumors, ensuring we’re not chasing phantom villains. Therapeutically, alpha‑blockers can coax the sphincter into a more cooperative posture, while anticholinergics calm the overzealous detrusor. Physical therapy, especially pelvic‑floor biofeedback, teaches patients to untangle the muscular knots that imprison urine. For those stubborn enough to resist, clean intermittent catheterization offers a safe bridge to prevent bladder over‑distension. Bottom line: a multifaceted assault on the root causes, paired with lifestyle tweaks like ditching caffeine, usually breaks the vicious cycle and restores dignity to bathroom visits.

Ash Charles

October 14, 2025 AT 12:55That was a marathon of info, but the takeaway is clear: a combo of meds, PT, and proper voiding habits usually does the trick. Stick to the plan and you’ll see improvement.

Michael GOUFIER

October 14, 2025 AT 21:15Let us rally together and apply these evidence‑based strategies; the path to a healthier bladder is within reach.

Spencer Riner

October 15, 2025 AT 05:35Curiosity drives us to ask why some patients develop chronic retention while others don’t. Could genetics be playing a hidden role? It’s worth digging deeper.

Joe Murrey

October 15, 2025 AT 13:55I get ur point but still think lifestyle tweaks matter a lot.

Tracy Harris

October 15, 2025 AT 22:15In the grand theatre of urology, the curtain rises on a drama of muscle and nerve, each demanding its own applause. The narrative, however, must not forget the silent actors-hydration habits and emotional stress-that shape the final act. Ignoring them would be a betrayal of comprehensive care.

debashis chakravarty

October 16, 2025 AT 06:35While the prose is eloquent, note the misuse of “its” versus “it’s” in the second sentence; precision matters when discussing clinical nuances.

Daniel Brake

October 16, 2025 AT 14:55One might contemplate the paradox that the bladder, a vessel of emptiness, becomes a source of profound anxiety when it refuses to empty.

Emily Stangel

October 16, 2025 AT 23:15From a holistic perspective, the interplay between physiological mechanisms and patient behavior cannot be overstated. When detrusor overactivity meets a hypertonic pelvic floor, the resulting obstruction resembles a perfect storm. Yet, the literature repeatedly emphasizes that modest adjustments-such as spacing fluid intake and refraining from late‑night caffeine-yield measurable benefits. Moreover, structured bladder training, wherein patients intentionally schedule voids, can recalibrate neural pathways over weeks. Physical therapy, especially with biofeedback, empowers individuals to actively relax the sphincter at the appropriate moment. Pharmacologic agents, while valuable, should be reserved for cases where conservative measures fail. Ultimately, the goal is to restore autonomy and prevent renal sequelae. Consistency, patience, and close follow‑up remain the cornerstones of success.

Vanessa Guimarães

October 17, 2025 AT 07:35Oh, sure, because “just relax” has cured everyone’s bladder woes, right? Let’s pretend we all have the time to meditate while our kidneys scream.

Lee Llewellyn

October 17, 2025 AT 15:55Honestly, the whole “bladder is a simple sack” narrative is a gross oversimplification that ignores the intricate neuro‑urodynamic feedback loops governing voiding. If you consider the evolutionary context, the pelvic floor evolved to protect against intra‑abdominal pressure spikes, not to serve as a choke point for urine. The medical community’s tendency to prescribe one‑size‑fits‑all pharmacotherapy reflects a deeper systemic inertia, where cost‑effectiveness outweighs individualized care. Moreover, the rising prevalence of over‑active bladder diagnoses correlates suspiciously with increased screen time and sedentary lifestyles, suggesting an environmental component that’s rarely acknowledged. Finally, patient education remains an achilles’ heel; many are unaware that seemingly benign habits-like excessive soda consumption-can precipitate chronic detrusor overactivity. In sum, a paradigm shift toward integrative, patient‑centered strategies is overdue.