There’s no such thing as a vaccine generic in the way you think of generic pills. You can’t just copy a vaccine the way you copy a cholesterol drug. Vaccines aren’t chemicals. They’re living systems-complex biological products made from viruses, bacteria, or mRNA instructions that tell your cells to build a defense. That’s why you can’t walk into a pharmacy and buy a cheaper version of the COVID-19 shot just because another company made it. The rules don’t work like that.

Why Vaccines Can’t Be Generic Like Pills

Generic drugs are simple compared to vaccines. A pill like metformin has one active ingredient. You can test it, measure it, and prove it works the same as the brand name. That’s the FDA’s ANDA process-Abbreviated New Drug Application. It’s been around since 1984. It saved the U.S. billions. Vaccines? Not even close. You can’t prove bioequivalence with a blood test. Each vaccine is a unique recipe of proteins, lipids, adjuvants, and stabilizers. Even tiny changes in temperature, mixing speed, or cell culture conditions can alter the final product. That’s why every new vaccine, no matter how similar, needs a full new license. No shortcuts. No generic pathway. The World Health Organization says it plainly: there’s no true ‘generics’ market for vaccines.Who Makes the World’s Vaccines?

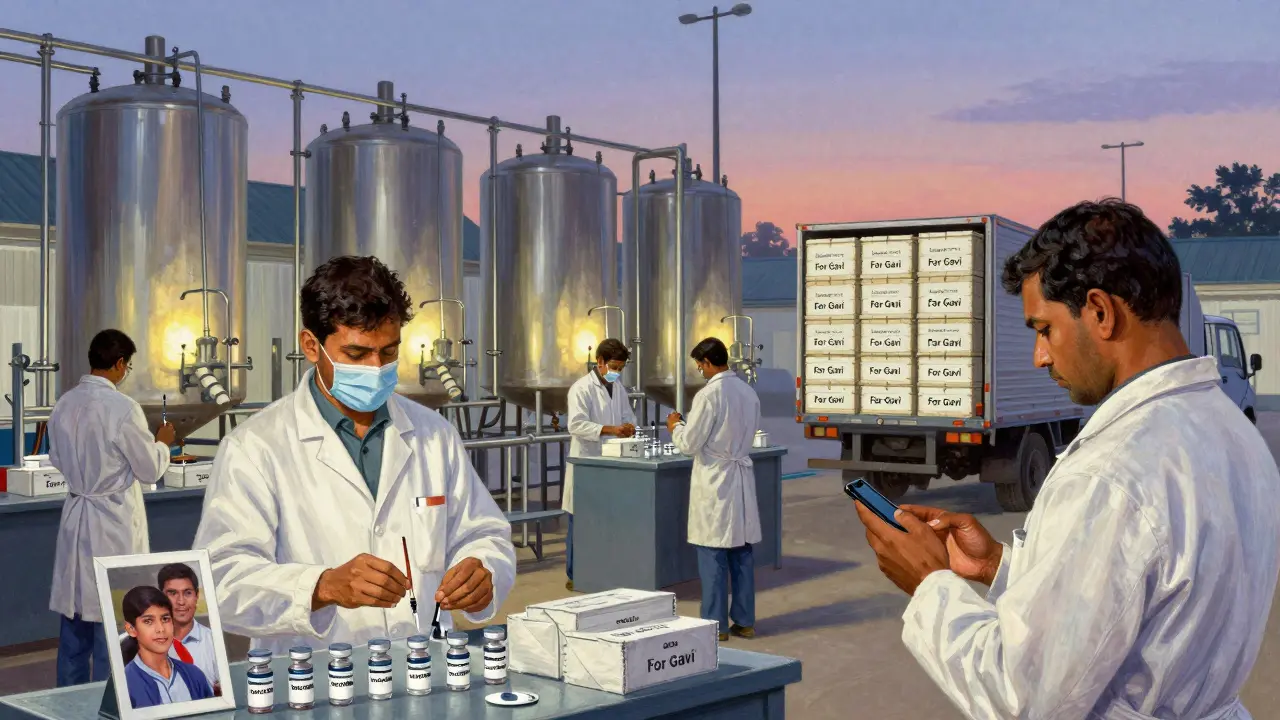

Just five companies-GSK, Merck, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson-controlled 70% of the global vaccine market in 2020. That’s $38 billion in sales. They’re not just big. They’re entrenched. Their factories cost half a billion dollars each. They have decades of experience, proprietary tech, and exclusive supply deals. And they’re mostly in Europe, North America, and a few places in Asia. Then there’s India. The Serum Institute of India (SII) is the largest vaccine maker in the world by volume. It produces 1.5 billion doses a year. It made the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine for less than $4 a dose-while Western makers charged $15 to $20. SII supplies 70% of the vaccines used by Gavi, the global vaccine alliance for low-income countries. It also makes 90% of the world’s measles vaccine. But here’s the catch: even with all that output, SII still imports 70% of its key raw materials from China. One export ban on a single lipid nanoparticle, and global supply can drop by half.The Supply Chain That Can’t Be Replicated

Making a vaccine isn’t like filling bottles with pills. It’s a six-month process. You need cell lines grown in sterile labs, purified with ultra-fine filters, mixed with lipid shells (for mRNA vaccines), and frozen at -70°C. That’s not just cold. That’s deep-freeze territory. Most clinics in rural Africa don’t have freezers that cold. Even if they had the vaccine, they couldn’t store it. The materials? Only five to seven companies worldwide can make the lipid nanoparticles needed for mRNA vaccines. If one shuts down, the whole system stutters. During the pandemic, the U.S. restricted exports of critical materials to India when its own cases spiked. That cut global vaccine supply by an estimated 50%. No one saw that coming. No one planned for it.

Why Africa Imports 99% of Its Vaccines

Africa produces 60% of the world’s vaccine volume-but almost none of it stays there. The continent imports 99% of the vaccines it uses. That’s not a mistake. It’s a system. African countries don’t have the factories, the equipment, or the supply chains. The African Union says it would take $4 billion and 10 years to get local production to 60% of needs. That’s a long time when kids are dying from preventable diseases. The WHO set up a mRNA tech transfer hub in South Africa in 2021 with help from BioNTech. Three years later, it produced its first mRNA vaccine. But it’s making 100 million doses a year. The world needs 11 billion. That’s less than 1%. The problem wasn’t the science. It was the parts. They couldn’t find the right bioreactors. The right filters. The right cold-chain packaging. Even with the blueprints, you can’t build a factory without the tools.Price Isn’t the Only Problem

People think if you make more vaccines, prices will drop. That’s true for pills. After five generic makers enter the market, a drug’s price can fall 90%. But vaccines? Not so much. Gavi, the global vaccine buyer, says the pneumococcal vaccine still costs over $10 per dose for poor countries-even after years of pressure. Why? Because the cost isn’t just the pill. It’s the factory, the cold chain, the safety checks, the transport. The profit margin is thin, but the fixed costs are huge. India’s SII makes vaccines at near-zero profit. They don’t make money on volume. They survive on scale and efficiency. But if a country like the U.S. decides to stockpile vaccines for itself, or if a raw material gets blocked, the whole system collapses. There’s no backup.

The Real Barrier: Capital, Not Knowledge

The idea that we just need to share the recipe is wrong. We’ve shared recipes. The WHO’s tech transfer hub in South Africa got the exact formula from BioNTech. The same for the one in Indonesia. But they’re still not making enough. Why? Because building a vaccine factory isn’t like setting up a website. It takes five to seven years. It needs $200 million to $500 million. It needs trained engineers, inspectors, and supply chain managers. It needs a government that will guarantee demand. The U.S. FDA admitted in 2025 that only 9% of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturers are in the U.S. Most are in India and China. That’s a national security risk. But fixing it? The FDA’s new pilot program gives faster approval to generics made in the U.S.-but that’s for pills. Not vaccines. The rules still don’t apply.What’s Actually Working?

The only real success story is India. It’s not because it’s cheap. It’s because it’s experienced. Indian manufacturers have been making vaccines for decades. They’ve built relationships with WHO, UNICEF, and Gavi. They’ve learned how to make millions of doses of DPT, BCG, and measles vaccines with minimal waste. They’ve survived export bans, pandemics, and political pressure. But even India can’t do it alone. It needs raw materials from China. It needs equipment from Germany. It needs cold-chain logistics from Denmark. No single country can be self-sufficient. The system is global-and fragile.The Future: More Factories, Not Just More Doses

By 2025, low- and middle-income countries will still be 70% dependent on imported vaccines. That’s the projection from Gavi. It’s not because they don’t want to make their own. It’s because they can’t. The money isn’t there. The expertise isn’t there. The supply chains aren’t there. The answer isn’t more charity. It’s more investment. More factories. More training. More local supply chains. The African Union’s plan to reach 60% self-sufficiency by 2040 is realistic-but only if the world actually pays for it. Right now, the system rewards big companies that can afford billion-dollar factories. It punishes countries that need vaccines the most. There’s no magic fix. No patent waiver will magically create a cold chain in rural Nigeria. No tech transfer will build a bioreactor out of thin air. The only thing that works is time, money, and a global commitment to build real capacity-not just donate doses.Right now, health workers in the Democratic Republic of Congo are getting vaccine doses that expire in two weeks because their clinics don’t have proper freezers. In Africa, 23 countries had vaccinated less than 2% of their people in April 2021, while 10 countries got 83% of the doses. That’s not a supply problem. That’s a justice problem.

There’s no such thing as a generic vaccine. But there should be a fair one.